Matthijs Nieuwkoop & Jos Havekotte predict the future (of meat alternatives) – part 2

- Jan Zandbergen

Part 2

In part 1, Matthijs Nieuwkoop advocated for a healthier perspective on health, especially when it comes to meat alternatives, because we now have an opportunity to truly replace meat. However, no matter how healthy a product is, if it’s not tasty, no one will buy it. But how do you develop a truly tasty meat substitute? During the opening event ‘The Taste of Innovation,’ Innovation Manager Jos Havekotte gave a lecture precisely on that topic. When the two stories of Jos and Matthijs are combined, a picture emerges of where these experts believe the future of plant-based protein sources should go. Today, part 2 of the two-part series: Jos Havekotte on the development of meat and fish alternatives.

Stagnating growth

Due to the tremendous growth of meat substitutes in supermarkets and restaurants, most consumers have likely purchased and tried a meat substitute by now. However, after years of growth, the market for meat alternatives is stagnating. What turns out to be the case is that, although everyone has tried meat substitutes, only 4% (!) of consumers repurchase them. The main obstacles are… taste and price. Consumers simply find many meat and fish substitutes disgusting. As mentioned in part 1 by Matthijs, supermarkets also opt for the cheapest product, which usually doesn’t go hand in hand with quality. Jos Havekotte, Innovation Manager at Jan Zandbergen Group, knows how to do it differently.

What is taste?

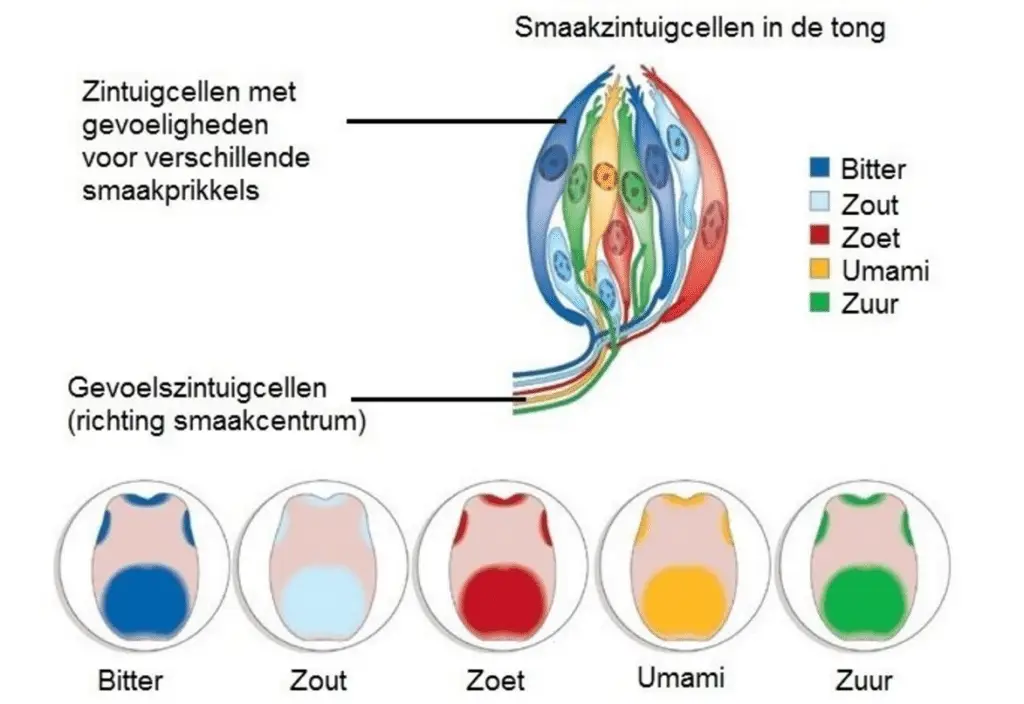

Traditionally, four primary tastes were distinguished: sweet, sour, salty, and bitter. Jos explains that this picture has been refined, as a fifth basic taste has been identified: umami, a word derived from the Japanese term for ‘delicious.’ Products with a high umami content are often perceived as ‘delicious.’ Think of salmon, beef, mushrooms, and truffles. Umami enhances the experience of savoury and sweet flavours in products.

‘Delicious’ may seem subjective and personal, but fortunately, there is also a more technical explanation of umami: the presence of one of the three amino acids: glutamate, inosine monophosphate, and guanosine monophosphate, occurring in products through processes such as salting, drying, aging, or fermenting. Jos states: “Because beef and pork also contain a high amount of umami, it is crucial to understand how this taste works and how we can apply this knowledge in developing tasty meat and fish alternatives that truly resemble meat.”

There’s no arguing about matters of taste, right?

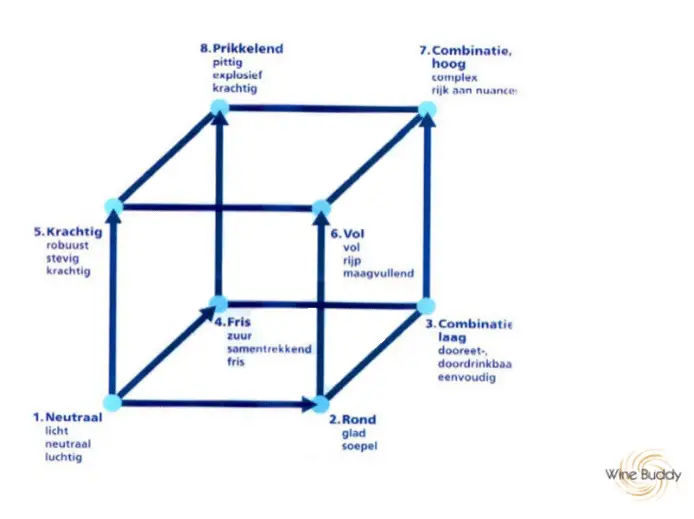

Taste may seem subjective and immeasurable, but appearances can be deceiving. Many researchers have attempted to categorize and classify tastes. For example, Jos referred to the taste cube developed by Dr. Peter Klosse in collaboration with Bob Cramwinckel from the Centre for Taste Research during his lecture. This cube categorizes tastes into 8 areas (see image). In practice, this cube is often used to pair wines with dishes. Additionally, the terms taste richness and taste type are important. Taste richness is the volume dial of taste: the intensity and quantity of flavour. Taste types are classified into two main categories: fresh notes (orange, apple, parsley, chives, raw onion) and ripe notes (rosemary, mushrooms, garlic, caramel, vanilla).

“Besides taste type and richness, mouthfeel is crucial to our taste experience. We distinguish three main types,” says Jos. A tight mouthfeel is caused by acids, salt, and carbonation. A coating mouthfeel is caused by dissolved sugars, fats, and proteins (a soft yolk). Lastly, a dry mouthfeel is experienced while eating the crispy crust of bread or fried meat. “These three types need to be in balance for a good taste experience. We repeatedly test products until we find the perfect balance between taste and mouthfeel.”

But how do you do it?

What does the process of developing a new product look like? With his years of experience, Jos has established a clear step-by-step plan for determining the taste of a product:

- Seek balance in basic tastes: sweet, salty, sour, bitter & umami.

- Ensure the correct mouthfeel: tight, coating, or dry.

- Determine the required taste style: a crab cake is relatively intense due to all the herbs, while a burger is often round and smooth.

- Determine the intensity of the flavour: for example, chicken fillet has a lower flavour intensity than beef.

- Identify any off-flavours: do you taste a flavour that shouldn’t be there?

- Determine salt content, any additional ingredients, and other additives.

“This step-by-step plan is a good starting point, but the most crucial part is yet to come!” says Jos. “Taste is not the only factor that determines whether a product is delicious. It sometimes happens that you think everything is perfect: the right ingredients in perfect balance, but during the taste test, the product is completely rejected.” Back to the drawing board we go. But where does it go wrong? “One word: texture.”

Structure is key

Jos Havekotte continues: “That first bite, it simply has to be right. That first bite determines whether you find something delicious. Meat has a unique and unmistakable structure, which we must approach as closely as possible if we truly want to replace meat.” According to Jos, structure might be the most important factor for the best experience right from the first bite: “Firm, crispy, intense, and flavourful, just like meat.” The spices and flavours you put into a product are soluble in a combination of fat and moisture (a gravy), so it’s important that there is enough moisture present in the structure.

During chewing, this moisture must be able to release to properly enhance the flavours. “We often see that the more gravy is released, the more intense the flavour, and the higher the consumer appreciation for that product,” says Jos. The structure of a product must be such that it can effectively retain the gravy and, at the same time, easily release it.

A dry structure can be influenced by adding more gravy to increase the juiciness of the product, but this also affects the flavour intensity and richness. This effect is not necessarily desirable. Jos explains: “For example: with a dry structure, more salt and more spices are needed to flavour the product properly. However, if you then improve the juiciness of this product, those spices are released better, and the product can suddenly taste overly intense and salty.” According to Jos, it is essential that when a product scores low on taste during a test or evaluation, the focus should first be on the structure and juiciness before adjusting the spice mix. In other words, structure comes first, taste comes second. “The proof of the pudding is in the eating,” Jos Havekotte concludes his lecture with a smile.

Bright Future (?)

The lectures by Matthijs and Jos demonstrate how complex it is to develop a product that can truly replace meat. Meat possesses unique qualities in terms of health and taste that people simply love. At Jan Zandbergen Group, we understand the importance of balance between meat and plant-based options. However, for people to buy and consume these alternatives, they must really be an alternative in terms of health and taste. That’s why we established the Future Food Group, to develop these true alternatives ourselves.

Based on the lectures by Matthijs and Jos, we can conclude that the key factors determining the success of meat alternatives are health and taste. This will not change in the future. In fact, consumers will become increasingly aware of the impact of food on their physical and mental health. However, it’s well-known that food choices are not made solely based on reason, and that’s what makes Jos’ story so relevant: taste is certainly a matter of debate. Above all, the products must be delicious. Therefore, it is particularly disappointing that most shelves are still filled with cheap, disgusting, and irresponsible meat substitutes just to enhance the supermarket’s green image. This is short-term thinking and will ultimately yield nothing for the retailer: customers won’t return for these products.

At Jan Zandbergen Group, we create meat and fish alternatives that meet the same high standards we apply to our meat. This requires an investment in ingredients, time, and money, resulting in a meat substitute that is beneficial for your health, the world, and tastebuds. Alright, perhaps we are not the cheapest, but we challenge retailers to show long-term vision because it can truly be done better, and Future Food Group demonstrates that!

Finally, let’s hear from our experts about where they think meat and fish alternatives are heading. Jos: “It is becoming increasingly clear to more and more consumers that the climate is permanently changing; we see it every day around us and in the news. As a result, the realization is growing that we really can change the way we contribute to climate change through the food we buy. Younger generations of consumers (Gen Z/Millennials) eat differently than their predecessors: much more vegan and in foodservice (fast service/On-The-Go). They are no longer programmed to consume meat as the ‘centre of the plate’ every day.”

Matthijs agrees: “The younger generation, in particular, realizes that it is not five minutes to midnight, but five minutes past, and this awareness will change consumption behaviour. In a few years, there won’t just be doomsayers warning us; we will see climate change happening right before our eyes. In fact, temperature records have already been broken all over the world in recent weeks. The only positive aspect of that is that it will accelerate the transition to a more sustainable dietary pattern.”

This is part two of a two-part series in which Matthijs Nieuwkoop and Jos Havekotte discuss their views on the health, taste, texture, and mouthfeel of meat alternatives while looking to the future. They gave these lectures at the opening event of Jan Zandbergen Group’s new Innovation Center: The Taste of Innovation. For more information about PLNT: